| |

Evolution vs. Intelligent Design

Scientific evidence that God is in the details

by Richard A. Wiedenheft

The theory of evolution by natural selection has dominated the

scientific world for almost a century and a half. And while most

evangelical Christians have always disparaged and dismissed the

theory, their arguments have done little to loosen its grip on

the thinking of most scientists, educators, and millions of their

students.

But now evolution is being challenged on a new front by

scientists themselves--not necessarily Chris-tians--who are part

of what is called the Intelligent Design (ID) movement. They

claim that evolution simply cannot explain the incredible

complexity and exquisite pattern so apparent in the natural

world. On the contrary, these could only be the result of

intelligent design.

The roots of this movement can perhaps be traced back to a book

written in 1984 by three scientists. These men challenged the

validity of experiments that supposedly demonstrated that life

could have arisen by chance from some primordial soup. Near the

end of their book they write:

A major conclusion to be drawn from this work is that the

undirected flow of energy through a primordial atmosphere and

ocean is at present a woefully inadequate explanation for the

incredible complexity associated with even simple living systems,

and is probably wrong.

and is probably wrong.1

In his 1996 book Darwin's Black Box, Michael Behe, professor of

biochemistry at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania,

puts it this way:

The simplicity that was once expected to be the foundation of

life has proven to be a phantom; instead, systems of horrendous,

irreducible complexity inhabit the cell. The resulting

realization that life was designed by an intelligence is a shock

to us in the twentieth century who have gotten used to thinking

of life as the result of simple natural laws.2

Irreducible complexity

One of the cornerstones of Behe's arguments is the concept of

irreducible complexity. A system or a mechanism can be reduced to

a point beyond which it becomes a pile of junk. He uses the

example of a mousetrap: It is so designed that removing any one

of its five essential parts renders it utterly useless for

catching mice. Either all the parts are present, properly

connected, and functioning, or the mousetrap doesn't work.

I like to illustrate this principle with a car. It's full of

devices and decorations that aren't essential for transportation.

The radio, the windows, and the chrome bumpers could

theoretically have been added over a long time by gradual

improvements and changes to a functioning car. But remove one of

the four wheels or the steering wheel or the flywheel, and you've

got an expensive pile of junk that won't go anywhere.

All the essential parts of an automobile have to be in place and

operating together at the same time, or it won't function at all

as a means of transport. You can't have a partially evolved

automobile that limps along somehow without any steering control

mechanism until some evolutionary process just happens to create

a steering wheel that just happens to be capable of transferring

its rotation to moveable wheels on the ground!

Geoffrey Simmons, M.D., calls this "all-or-none," or

the "whole-package phenomenon (WPP)."3 The whole

package has to be in place, or nothing gets accomplished.

The living world is full of "whole packages"--intricate

yet irreducibly complex mechanisms and processes. These present a

huge problem for the theory of evolution, which posits that

complex forms of life can develop step by step from simpler

forms, gradually adding functionality as they become more and

more complicated. As Behe says:

An irreducibly complex system cannot be produced directly... by

slight, successive modifications of a precursor system, because

any precursor to an irreducibly complex system that is missing a

part is by definition nonfunctional.4

Even Charles Darwin recognized this "Achilles' heel" of

his theory. Behe quotes from The Origin of the Species: "If

it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which

could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive,

slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break

down."5

In Darwin's day, however, scientists were just beginning to

recognize that living organisms were made of cells, which they

understood little about. The cell was an unknown or, as Behe

terms it, a "black box." The presumption was that once

they came to understand the cell, scientists would find simple

structures and processes that would support the theory of

evolution.

"Simple" cells

When I studied biology in high school and college in the 1960s,

teachers talked of simple cells and simple one-celled animals.

The thinking was that amino acids somehow developed into

uncomplicated functioning cells, which eventually adapted to

their environment to become more complicated cells, which

developed into multi-cellular plants and animals—and on and

on until all the life forms as we know them today were developed.

So the theory went.

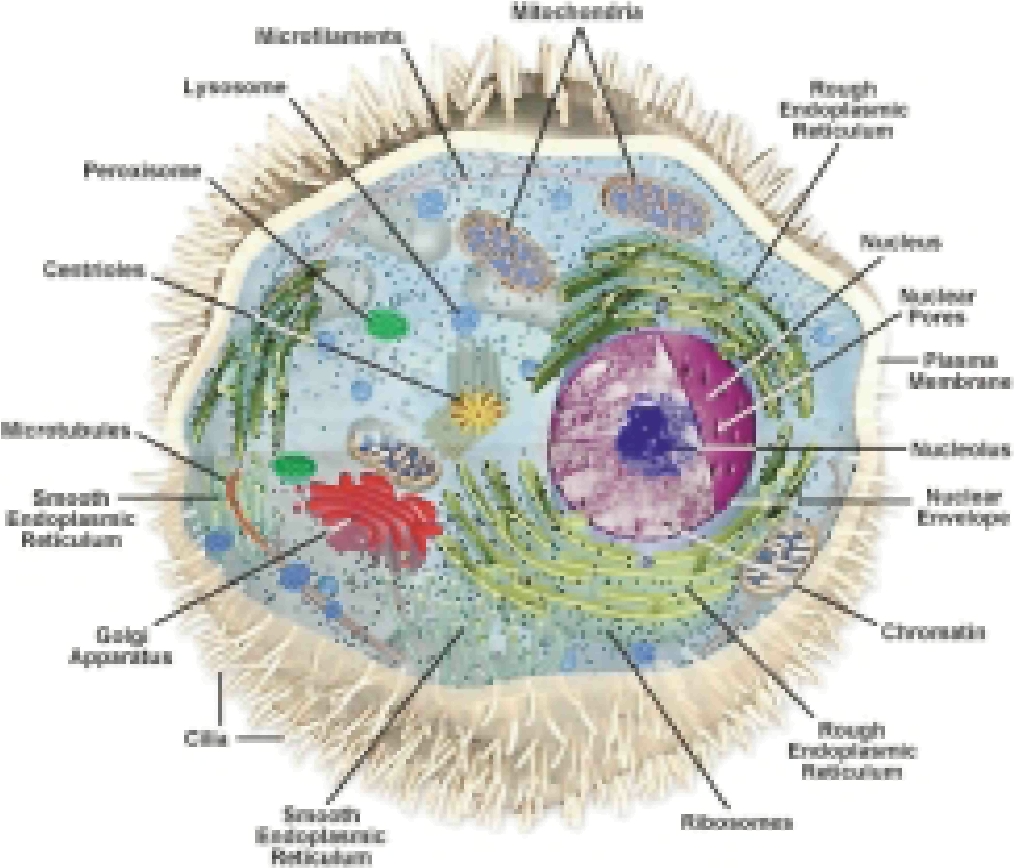

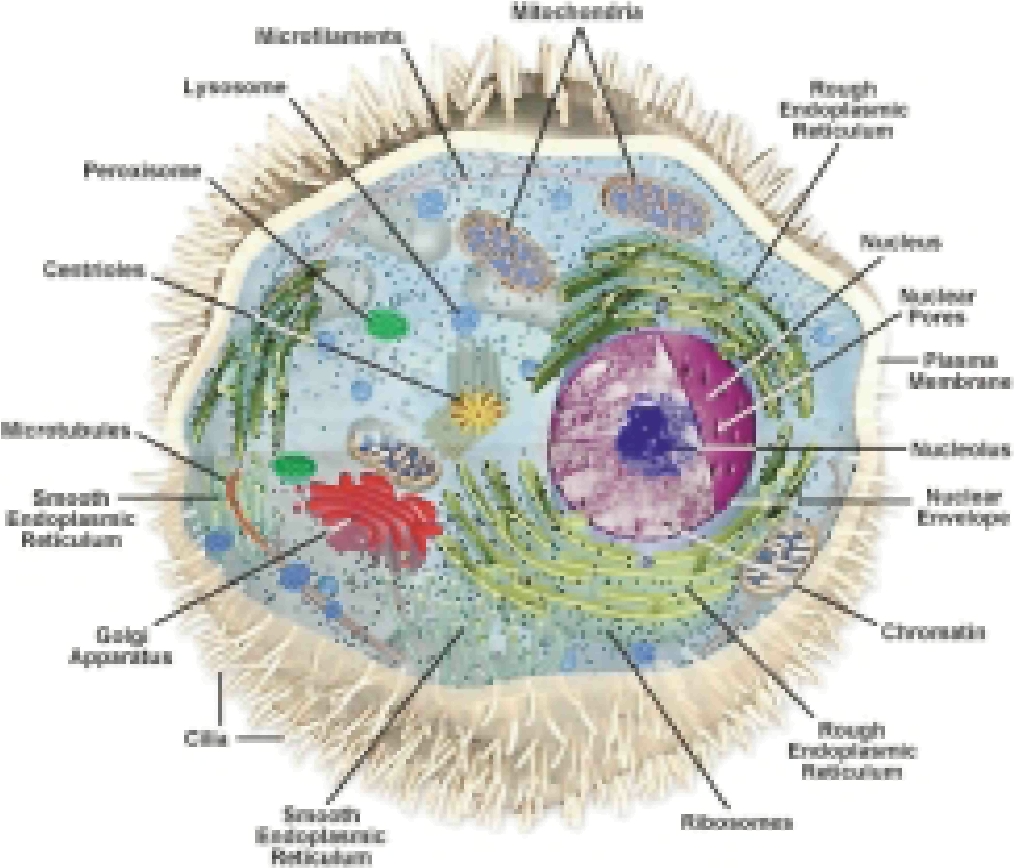

However, with the advent of the electron microscope in the

mid-twentieth century, scientists could begin to open the

"black box" of the cell. Around the same time, X-ray

crystallography enabled researchers to determine the structure of

various molecules, including complex protein molecules. These

advances revealed far more complexity than anyone had ever

imagined. The simplest of cells is anything but simple.

Geoffrey Simmons estimates that every

cell contains one billion compounds including five million

different kinds of proteins, each one having a unique shape and

characteristics that enable it to play a specific role in the

body. In addition, there are more than 3,000 enzymes critical to

chemical reactions that take place in the body. Cells come in

many varieties and shapes; they serve many different and

specialized functions in the body. Some cells work as individuals

floating in the blood; others connect with identical cells to

form skin or muscles, for example. Still others send out long

extensions to communicate with other cells.6 Geoffrey Simmons estimates that every

cell contains one billion compounds including five million

different kinds of proteins, each one having a unique shape and

characteristics that enable it to play a specific role in the

body. In addition, there are more than 3,000 enzymes critical to

chemical reactions that take place in the body. Cells come in

many varieties and shapes; they serve many different and

specialized functions in the body. Some cells work as individuals

floating in the blood; others connect with identical cells to

form skin or muscles, for example. Still others send out long

extensions to communicate with other cells.6

When one looks into the workings of any one cell, he finds

incredible complexity.

The "simplest" self-sufficient, replicating cell has

the capacity to produce thousands of different proteins and other

molecules, at different times and under variable conditions.

Synthesis, degradation, energy generation, replication,

maintenance of cell architecture, mobility, regulation, repair,

communication--all of these functions take place in virtually

every cell, and each function itself requires the interaction of

numerous parts.7

Behe likens all this activity, accomplished at the molecular

level, to the workings of machinery:

... life is based on machines—machines made of molecules!

Molecular machines haul cargo from one place in the cell to

another along "highways" made of other molecules, while

still others act as cables, ropes, and pulleys to hold the cell

in shape. Machines turn cellular switches on and off, sometimes

killing the cell or causing it to grow. Solar-powered machines

capture the energy of photons and store it in chemicals.

Electrical machines allow current to flow through nerves.

Manufacturing machines build other molecular machines, as well as

themselves. Cells swim using machines, copy themselves with

machinery, ingest food with machinery. In short, highly

sophisticated molecular machines control every cellular process.

Thus the details of life are finely calibrated, and the machinery

of life enormously complex.8

In other words, the simplest cell is a veritable factory of

molecular machines, and evolution offers no mechanism whereby

this factory could have gradually assembled itself over long

periods of time.

Conceptual precursors are not physical precursors

Behe faults evolutionists for failing to look at the details when

they postulate how, for example, a single-celled animal with a

light-sensitive spot could, over a very long time, develop into

an eye. The light-sensitive spot might be a conceptual precursor

to an eye, but when one looks at all the chemical systems in the

eye, there is no way the light-sensitive spot could be a physical

precursor to the eye.

As an illustration, consider the bicycle as a conceptual

precursor to a simple motorized bike. One could postulate that

somehow the bicycle gradually developed into a motor bike. But

looking deeper, one discovers that this progression simply cannot

happen gradually. The motor, for example, is an entire

irre-ducibly complex system consisting of hundreds of parts. If

any one part is missing (a spark plug, for example), the motor is

useless. And even if the motor were somehow available in an

evolutionary junkyard, it would have to be securely mounted on

the frame, and somehow transfer its energy to a drive sprocket,

which would somehow get connected to a wheel sprocket in order to

make a wheel turn. Then there's the problem of fuel, carburetion,

and a starting mechanism. Without all the parts fully assembled,

the motor bike won't function at all. Gradually adding some parts

without the others results in a more cumbersome conveyance that

is less functional than the original bicycle.

The bicycle may help us to conceive of, to conceptualize, a motor

bike, but it cannot be a physical precursor to a motor bike.

Similarly, the light-sensitive spot may be a conceptual precursor

to an eye, but it would have to add many complex functions and

biochemical processes, each of them irreducibly complex, in order

to function as an eye. Evolution is based on the assumption of

physical precursors. But the natural world offers irreducibly

complex systems that function only as a whole and that could have

come about only by Intelligent Design.

An example: cilia

For us non-biochemists, the details of how the body functions at

the molecular level can be hard to grasp. But it is in the

details that evolution faces its greatest challenges, and it is

in the details that we can see the marvel of a creation that

cries out for intelligent design.

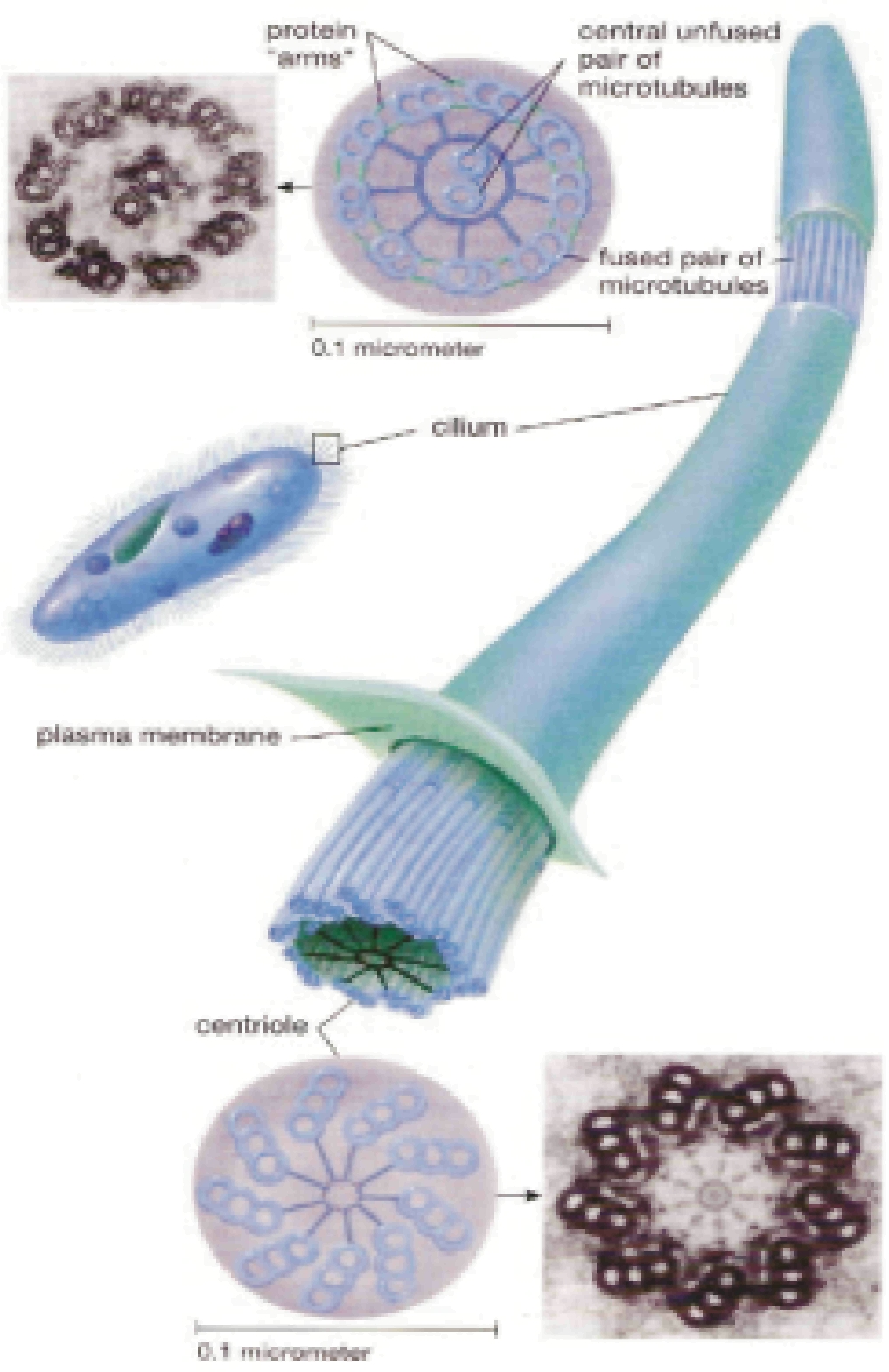

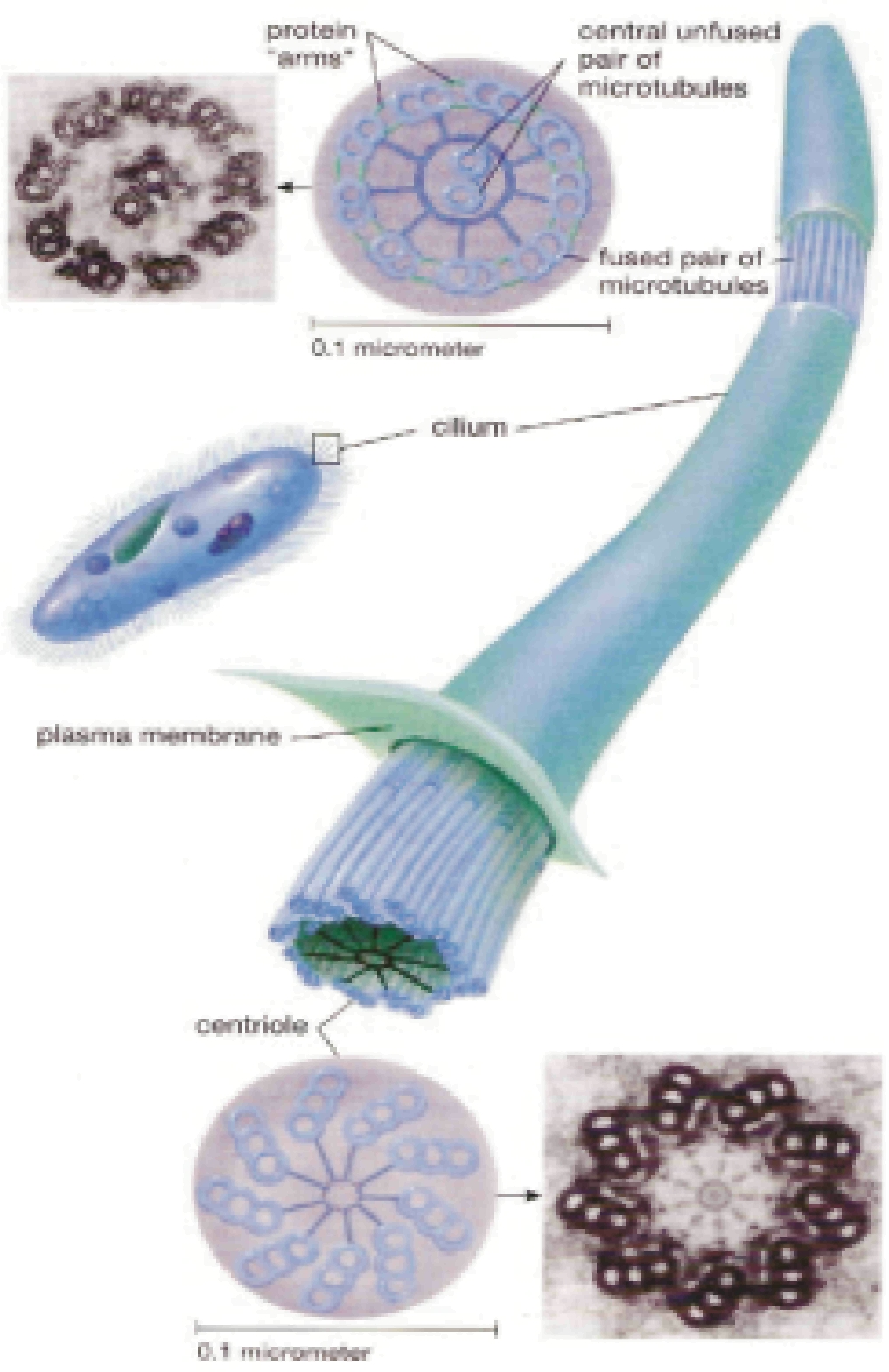

One example of an irreducibly complex system, detailed by Behe,

is cilia—cells with hair-like extensions that can move like

a whip. The respiratory tract is lined with cilia, helping expel

mucus. Sperm cells are mobile and have cilia to swim. These

apparently simple cells are actually complex molecular machines.

If you cut through a cilium and examine its cross section under

great magnification, you discover that it is composed of a number

of tiny tubes, or microtu-bules. Just inside the "skin"

of the cilium is a circle of nine pairs of these tiny tubes. In

the middle of the cilium is yet another set of two microtubules

linked to each other. All the microtubules are, in fact,

cylinders made up by a circle of even smaller strands or fibers.

The current understanding of biochemists is that the motion of

the cilium depends on two protein molecules that go between a

microtubule of one pair and one of the microtubules of the pair

next to it. One of these proteins is dynein, the

"motor" of the cilium. The other is nexin, which serves

as a link or tie between the adjacent pairs.

Under the right circumstances, the dynein pushes against the

molecules in the microtubule next to it so that the two tend to

slide past one another. In fact, if the microtubule pairs weren't

tied together by the nexin, the dynein molecules would just keep

pushing the adjacent tubule along like a telescoping antenna

until they reached the end. But the nexin connectors prevent that

from happening. With the dynein pushing and the nexin holding,

the microtubules bend. This action of all the dynein motors

pushing over and over again and all the nexin linkers holding on

tight is apparently what makes cilia whip and the cell move.

This is a simplified

explanation of an intricate mechanism, one that, according to

Behe, is irreducibly complex. This is a simplified

explanation of an intricate mechanism, one that, according to

Behe, is irreducibly complex.

All of these parts are required to perform one function: ciliary

motion. Just as a mousetrap does not work unless all of its

constituent parts are present, ciliary motion simply does not

exist in the absence of microtubles, connectors, and motors.

Therefore we can conclude that the cilium is irreducibly

complex—an enormous monkey wrench thrown into its presumed

gradual, Darwinian evolution.9

The Clotting of Blood

When you get cut, your life depends on the ability of your blood

to quickly form a clot before all your blood drains out. Just as

important, it has to stop clotting when the bleeding is stopped,

and it has to not clot when there's no wound! That seems like a

relatively simple assignment, but it is not. On the contrary, the

body's mechanism for controlling blood clotting is a marvelous

and intricate series of chemical reactions that is irreducibly

complex. Remove any one of the elements, and blood clotting

simply doesn't work.

Fibrogen is the protein that is used to make up the web, or mesh,

of "fibers" that plays a vital role in clot formation.

Normally, it just floats around in the blood. In order for it to

get involved in clotting, fibrogen has to be altered by another

protein, thrombin, which lops off small pieces of the fibrogen

molecule to expose "sticky patches." This new molecule

is called fibrin. Its sticky patches fit into portions of other

fibrin molecules so they begin to form long strands that cross

over one another to form a web that traps blood cells.

But what keeps the thrombin from lopping off the ends of the

fibrogen molecule all the time creating one massive blood clot?

The answer is that thrombin molecules float around in the

bloodstream in an inactive form called prothrombin. It takes

another protein, called Stuart's Factor, to activate prothrombin.

But what keeps Stuart's Factor from activating prothrombin all

the time? That involves yet another protein molecule, accelerin,

which exists in an inactive form until it is activated

by—well, you get the picture!

In all, there are some twenty chemicals involved in the cascade

of reactions that quickly swings into action when the body is

wounded. The clotting mechanism first forms a soft clot to stop

the flow of blood. Then it turns off the clotting process, then

converts the fragile soft clot into a hard one that is more

durable. Finally, when the wound is healed, it breaks up the

clot. All the chemicals involved are essential to the process. If

any one is missing, the entire process fails to work.

Hemophiliacs, for example, can't stop bleeding because their

blood lacks one of these essential factors.

Referring to the effort of one scientist to explain how this

blood clotting cascade could have evolved gradually, Behe wrote:

The fact is, no one on earth has the vaguest idea how the

coagulation cascade came to be.... Blood coagulation is a

paradigm of the staggering complexity that underlies even

apparently simple bodily processes. Faced with such complexity

beneath even simple phenomena, Darwinian theory falls

silent."10

Other examples of complexity

Behe details other examples of irreducibly complex systems in the

body, including the seemingly simple task of moving proteins

created in one part of a cell to another part of the cell where

they are needed. One method, which he calls a "mind-boggling

process," is vesicular transport

... where protein cargo is loaded into containers for shipment

[from one part of the cell to another].... An analysis shows that

vesicular transport is irreducibly complex, and so its

development staunchly resists gradualistic explanations, as

Darwinian evolution would have it.11

Simmons cites insulin production as a process that is irreducibly

complex as well:

In the process of insulin manufacture, none of the several

"pre-insulin" molecules are useful (envision a car

being made along an assembly line). Not only is this an

all-or-none process, but so are the mechanisms that tell the body

when to secrete insulin, how much insulin to produce or secrete,

for how long, where to send it, how to link it to nutrients in

the blood, how to transport it, and how to turn it off when the

job is done.12

Then, there's the body's immune system and the manufacture of

AMP, a form of one of the four building blocks used to make up

DNA. These are all very complicated, yet irreducible; and

evolutionists offer no explanation as to how they came about.

What does it all mean?

In his conclusion, Behe writes about the implications of all the

knowledge about cell structure and function that has been

accumulated over the past four decades.

The result of these cumulative efforts to investigate the

cell--to investigate life at the molecular level— is a loud,

clear, piercing cry of "design!" The result is so

unambiguous and so significant that it must be ranked as one of

the greatest achievements in the history of science.... The

observation of the intelligent design of life is as momentous as

the observation that the earth goes around the sun or that

disease is caused by bacteria or that radiation is emitted in

quanta.... But no bottles have been uncorked, no hands slapped

[to celebrate this discovery]. Instead, a curious, embarrassed

silence surrounds the stark complexity of the cell.... Why does

the scientific community not greedily embrace its startling

discovery? ... The dilemma is that while one side of the elephant

is labeled intelligent design, the other side might be labeled

God.13

Behe finds this rather odd given the fact that 90 percent of

Americans say they believe in God and about 50 percent attend

religious services every week and that you regularly hear

references to God from politicians and sports stars.

But the apostle Paul would certainly not have been surprised. He

wrote almost 2,000 years ago of those who "did not like to

retain God in their knowledge" (Romans 1:28). And while the

intelligent design movement is a serious challenge to evolution,

I don't think we should be optimistic that Darwin's theory will

collapse anytime soon, nor that large numbers of scientists will

embrace God as the Intelligent Designer. The mainstream of

society didn't pay much attention to God before Darwin, and I

doubt it will pay much attention after his theory is relegated to

the footnotes of the history of science.

On the other hand, Christians can have greater confidence that

our belief in God is not based on a blind faith that is in

conflict with science. On the contrary, we can glorify God with

the psalmist: "I praise you because I am fearfully and

wonderfully made; your works are wonderful, I know that full

well" (Psalm 139:14, NIV). With every advance of science in

understanding the intricate design of the creation, we know more

and more "full well" how wonderful the Creator is.

For since the creation of the world God's invisible

qualities—-his eternal power and divine nature—-have

been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so

that men are without excuse (Romans 1:20).

The more we learn of the exquisite, fantastic design of the

creation, the more clearly we can see the magnitude of the

Creator's eternal power and majesty!

References

1. Charles B. Thaxton, Walter L. Bradley, Roger L. Olsen, The

Mystery of Life's Origin: Reassessing Current Theories, p. 186

2. Michael J. Behe, Darwin's Black Box, The Biochemical Challenge

to Evolution (The Free Press, 2003), p. 252

3. Geoffrey Simmons, M.D., What Darwin Didn't Know, p. 34

4. Behe, Darwin's Black Box, The Biochemical Challenge to

Evolution, p. 39

5. Ibid.

6. Simmons, What Darwin Didn't Know, pp. 43, 44

7. Ibid., p. 46

8. Behe, Darwin's Black Box, The Biochemical Challenge to

Evolution, pp. 4-5

9. Ibid. p. 65

10. Ibid., p. 97

11. Ibid. pp. 109, 115

12. Simmons, What Darwin Didn't Know, p. 37

13. Ibid. pp. 232-233

Richard A. Wiedenheft and his wife, Darlene, live in Falls, PA.

This article is reprinted by permission and is taken from the

March 2005 edition of The Bible Advocate. © 2005 The General

Conference of the Church of God (Seventh Day)

"We have a strange illusion that mere time cancels sin. I

have heard others, and I have heard myself, recounting cruelties

and falsehoods committed in boyhood as if they were not the

concern of the present speakers, and even with laughter. But mere

time does nothing either to the fact or to the guilt of a sin.

The guilt is washed out not by time but by repentance and the

blood of Christ." —C. S. Lewis

TSS

July

/ August 2005 The Sabbath Sentinel

|

Geoffrey Simmons estimates that every

cell contains one billion compounds including five million

different kinds of proteins, each one having a unique shape and

characteristics that enable it to play a specific role in the

body. In addition, there are more than 3,000 enzymes critical to

chemical reactions that take place in the body. Cells come in

many varieties and shapes; they serve many different and

specialized functions in the body. Some cells work as individuals

floating in the blood; others connect with identical cells to

form skin or muscles, for example. Still others send out long

extensions to communicate with other cells.6

Geoffrey Simmons estimates that every

cell contains one billion compounds including five million

different kinds of proteins, each one having a unique shape and

characteristics that enable it to play a specific role in the

body. In addition, there are more than 3,000 enzymes critical to

chemical reactions that take place in the body. Cells come in

many varieties and shapes; they serve many different and

specialized functions in the body. Some cells work as individuals

floating in the blood; others connect with identical cells to

form skin or muscles, for example. Still others send out long

extensions to communicate with other cells.6

This is a simplified

explanation of an intricate mechanism, one that, according to

Behe, is irreducibly complex.

This is a simplified

explanation of an intricate mechanism, one that, according to

Behe, is irreducibly complex.